Why Do I Continue to Burp

Inability to Burp or Belch

Inability to burp or belch occurs when the upper esophageal sphincter (cricopharyngeus muscle) cannot relax in order to release the "bubble" of air. The sphincter is a muscular valve that encircles the upper end of the esophagus just below the lower end of the throat passage. If looking from the front at a person's neck, it is just below the "Adam's / Eve's apple," directly behind the cricoid cartilage.

If you care to see this on a model, look at the photos below. That sphincter muscle relaxes for about a second every time we swallow saliva, food, or drink. All of the rest of the time it is contracted. Whenever a person belches, the same sphincter needs to let go for a split second in order for the excess air to escape upwards. In other words, just as it is necessary that the sphincter "let go" to admit food and drink downwards in the normal act swallowing, it is also necessary that the sphincter be able to "let go" to release air upwards for belching. The formal name for this disorder is retrograde cricopharyngeus dysfunction (R-CPD).

People who cannot release air upwards are miserable. They can feel the "bubble" sitting at the mid to low neck with nowhere to go. Or they experience gurgling when air comes up the esophagus only to find that the way of escape is blocked by a non-relaxing sphincter. It is as though the muscle of the esophagus continually churns and squeezes without success.

The person so wants and needs to burp, but continues to experience this inability to burp. Sometimes this can even be painful. Such people often experience chest pressure or abdominal bloating, and even abdominal distention. Flatulence is also severe in most persons with R-CPD. Other less universal symptoms are nausea after eating, painful hiccups, hypersalivation, or a feeling of difficulty breathing with exertion when "full of air." Many persons with R-CPD have undergone extensive testing and treatment trials without benefit.R-CPD reduces quality of life, and is often socially disruptive and anxiety-provoking. Common (incorrect) diagnoses are "acid reflux" and "irritable bowel syndrome," and therefore treatments for these conditions do not relieve symptoms significantly.

Approaches for treating the inability to burp:

For people who match the syndrome of:

1) Inability to belch

2) Gurgling noises

3) Chest/abdominal pressure and bloating

4) Flatulence

Here is the most efficient way forward: First, a consultation to determine whether or not the criteria for diagnosing R-CPD are met. Next, a simple office-based videoendoscopic swallow study which incorporates a neurological examination of tongue, pharynx (throat) and larynx muscles and often includes a mini-esophagoscopy. This establishes that the sphincter works normally in a forward (antegrade) swallowing direction, but not in a reverse (retrograde) burping or regurgitating fashion. Along with the symptoms described above, this straightforward office consultation and swallowing evaluation establishes the diagnosis of retrograde cricopharyngeus dysfunction (non-relaxation).

The second step is to place Botox into the malfunctioning sphincter muscle. The desired effect of Botox in muscle is to weaken it for at least several months. The person thus has many weeks to verify that the problem is solved or at least minimized.

The Botox injection could potentially be done in an office setting, but we recommend the first time (at least) placing it during a very brief general anesthetic in an outpatient operating room. That's because the first time, it is important to answer the question definitively, that is, that the sphincter's inability to relax when presented with a bubble of air from below, is the problem. Furthermore, based upon an experience with more than 890 patients as of August 2019, a single injection appears to "train" the patient how to burp. Approximately 80% of patients have maintained the ability to burp long after the effect of the Botox has dissipated. That is, long past 6 months from the time of injection.

Patients treated for R-CPD as just described should experience dramatic relief of their symptoms. And to repeat, our experience in treating more than 890 patients (and counting) suggests that this single Botox injection allows the system to "reset" and the person may never lose his or her ability to burp. Of course, if the problem returns, the individual could elect to pursue additional Botox treatments, or might even elect to undergo endoscopic laser cricopharyngeus myotomy. To learn more about this condition, see Dr. Bastian's description of his experience with the first 51 of his much larger caseload.

R-CPD Webinar + Q&A

Where is the Cricopharyngeus Muscle?

Cricopharyngeus Muscle (1 of 3)

The highlighted oval represents the location of the cricopharyngeus muscle.

Cricopharyngeus Muscle (2 of 3)

The cricopharyngeus muscles in the open position.

Contracted Cricopharyngeus Muscle (3 of 3)

The cricopharyngeus muscle in the contracted position.

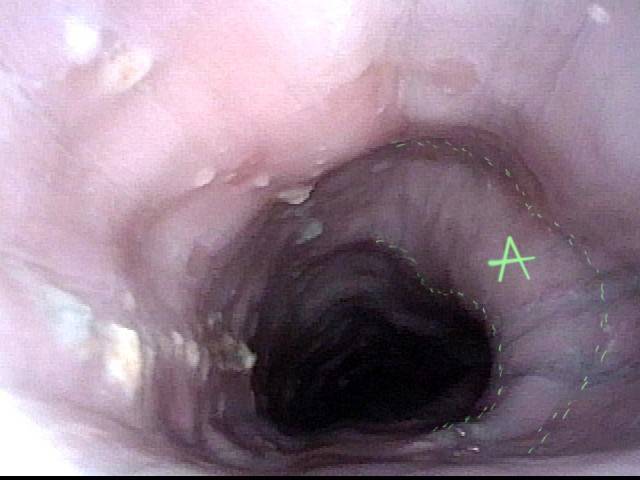

Aortic shelf (1 of 3)

A view of the mid-esophagus in a young person (early 30's). The esophagus is kept open by the patient's un-burped air. Note the "aortic shelf" at A, delineated by dotted lines.

Aortic shelf (1 of 3)

A view of the mid-esophagus in a young person (early 30's). The esophagus is kept open by the patient's un-burped air. Note the "aortic shelf" at A, delineated by dotted lines.

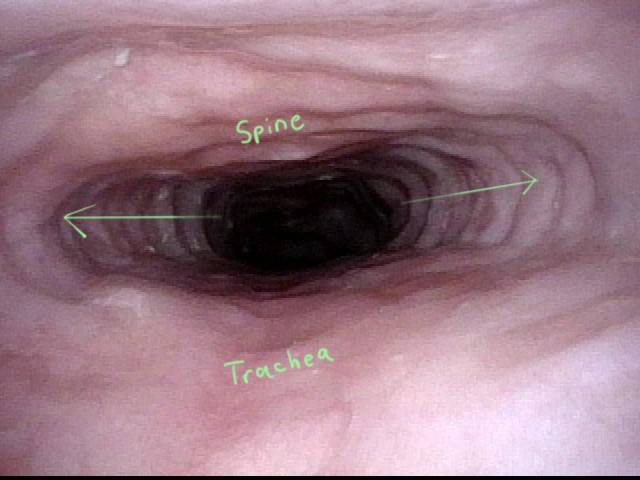

Bony spur emerges due to stretched esophagus (2 of 3)

A moment later, additional air is pushed upwards from the stomach to dilate the mid-esophagus even more. A bony "spur" in the spine is thrown into high relief by the stretched esophagus.

Stretched esophagus due to unburpable air (3 of 3)

A view of the upper esophagus (from just below the cricopharyngeus muscle sphincter) shows what appears to be remarkable lateral dilation (arrows) caused over time by the patient's unburpable air. Dilation can only occur laterally due to confinement of the esophagus by trachea (anteriorly) and spine (posteriorly), as marked.

Stretched esophagus due to unburpable air (3 of 3)

A view of the upper esophagus (from just below the cricopharyngeus muscle sphincter) shows what appears to be remarkable lateral dilation (arrows) caused over time by the patient's unburpable air. Dilation can only occur laterally due to confinement of the esophagus by trachea (anteriorly) and spine (posteriorly), as marked.

Abdominal Distention of R-CPD

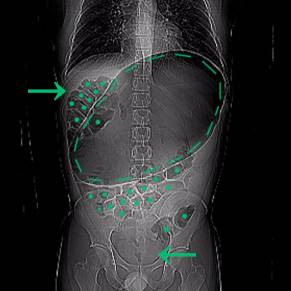

Gastric Air Bubble (1 of 3)

This abdominal xray of an individual with R-CPD shows a remarkably large gastric air bubble (dotted line), and also excessive air in transverse (T) and descending (D) colon. All of this extra air can cause abdominal distention that increases as the day progresses.

Gastric Air Bubble (1 of 3)

This abdominal xray of an individual with R-CPD shows a remarkably large gastric air bubble (dotted line), and also excessive air in transverse (T) and descending (D) colon. All of this extra air can cause abdominal distention that increases as the day progresses.

Bloated Abdomen (2 of 3)

Flatulence in the evening and even into the night returns the abdomen to normal, but the cycle repeats the next day. To ask patients their degree of abdominal distention, we use pregnancy as an analogy in both men and women. Not everyone describes this problem. Most, however, say that late in the day they appear to be "at least 3 months pregnant." Some say "6 months" or even "full term." In a different patient with untreated R-CPD, here is what her abdomen looked like late in every day. Her abdomen bulges due to all of the air in her GI tract, just as shown in Photo 1.

Bloated Abdomen (2 of 3)

Flatulence in the evening and even into the night returns the abdomen to normal, but the cycle repeats the next day. To ask patients their degree of abdominal distention, we use pregnancy as an analogy in both men and women. Not everyone describes this problem. Most, however, say that late in the day they appear to be "at least 3 months pregnant." Some say "6 months" or even "full term." In a different patient with untreated R-CPD, here is what her abdomen looked like late in every day. Her abdomen bulges due to all of the air in her GI tract, just as shown in Photo 1.

Non-bloated Abdomen (3 of 3)

The same patient, a few weeks after Botox injection. She is now able to burp. Bloating and flatulence are remarkably diminished, and her abdomen no longer balloons towards the end of every day.

Non-bloated Abdomen (3 of 3)

The same patient, a few weeks after Botox injection. She is now able to burp. Bloating and flatulence are remarkably diminished, and her abdomen no longer balloons towards the end of every day.

A Rare "abdominal crisis" Due to R-CPD (inability to burp)

X-Ray of Abdominal Bloating (1 of 2)

This young man had an abdominal crisis related to R-CPD. He has had lifelong symptoms of classic R-CPD: inability to burp, gurgling, bloating, and flatulence. During a time of particular discomfort, he unfortunately took a "remedy" that was carbonated. Here you see a massive stomach air bubble. A lot of his intestines are air-filled and pressed up and to his right (left of photo, at arrow). The internal pressure within his abdomen also shut off his ability to pass gas. Note arrow pointing to lack of gas in the descending colon/rectum. NG decompression of his stomach allowed him to resume passing gas, returning him to his baseline "daily misery" of R-CPD.

X-Ray of Abdominal Bloating (1 of 2)

This young man had an abdominal crisis related to R-CPD. He has had lifelong symptoms of classic R-CPD: inability to burp, gurgling, bloating, and flatulence. During a time of particular discomfort, he unfortunately took a "remedy" that was carbonated. Here you see a massive stomach air bubble. A lot of his intestines are air-filled and pressed up and to his right (left of photo, at arrow). The internal pressure within his abdomen also shut off his ability to pass gas. Note arrow pointing to lack of gas in the descending colon/rectum. NG decompression of his stomach allowed him to resume passing gas, returning him to his baseline "daily misery" of R-CPD.

X-Ray of Abdominal Bloating (2 of 2)

X-Ray without markings

Play Video about R-CPD in X-ray Pictures: Misery vs. Crisis from Inability to Burp

Can't Burp: Progression of Bloating and Abdominal Distention

— A Daily Cycle for Many with R-CPD

This young woman has classic R-CPD symptoms—the can't burp syndrome. Early in the day, her symptoms are least, and abdomen at "baseline" because she has "deflated" via flatulence through the night. In this series you see the difference in her abdominal distention between early and late in the day. The xray images show the remarkable amount of air retained that explains her bloating and distention. Her progression is quite typical; some with R-CPD distend even more than shown here especially after eating a large meal or consuming anything carbonated.

Side view of a bloated abdomen (1 of 6)

Early in the day, side view of the abdomen shows mild distention. The patient's discomfort is minimal at this time of day as compared with later.

Mild distension (2 of 6)

Also early in the day, a front view, showing again mild distention.

Front view (3 of 6)

Late in the same day, another side view to compare with photo 1. Accumulation of air in stomach and intestines is distending the abdominal wall.

Front view (3 of 6)

Late in the same day, another side view to compare with photo 1. Accumulation of air in stomach and intestines is distending the abdominal wall.

Another view (4 of 6)

Also late in the day, the front view to compare with photo 2, showing considerably more distention. The patient is quite uncomfortable, bloated, and feels ready to "pop." Flatulence becomes more intense this time of day, and will continue through the night.

Another view (4 of 6)

Also late in the day, the front view to compare with photo 2, showing considerably more distention. The patient is quite uncomfortable, bloated, and feels ready to "pop." Flatulence becomes more intense this time of day, and will continue through the night.

X-ray of trapped air (5 of 6)

Antero-posterior xray of the chest shows a very large stomach air bubble (at *) and the descending colon is filled with air (arrow).

X-ray of trapped air (5 of 6)

Antero-posterior xray of the chest shows a very large stomach air bubble (at *) and the descending colon is filled with air (arrow).

Side view (6 of 6)

A lateral view chest xray shows again the large amount of excess air in the stomach and intestines that the patient must rid herself of via flatulence, typically including through the night, in order to begin the cycle again the next day.

Side view (6 of 6)

A lateral view chest xray shows again the large amount of excess air in the stomach and intestines that the patient must rid herself of via flatulence, typically including through the night, in order to begin the cycle again the next day.

Shortness of Breath Caused by No-Burp (R-CPD)

Persons who can't burp and have the full-blown R-CPD syndrome often say that when the bloating and distention are particularly bad—and especially when they have a sense of chest pressure, they also have a feeling of shortness of breath. They'll say, for example, "I'm a [singer, or runner, or cyclist or _____], but my ability is so diminished by R-CPD. If I'm competing or performing I can't eat or drink for 6 hours beforehand." Some even say that they can't complete a yawn when symptoms are particularly bad. The X-rays below explain how inability to burp can cause shortness of breath.

X-ray of trapped air (1 of 2)

Antero-posterior xray of the chest shows a very large stomach air bubble (at *) and the descending colon is filled with air (arrow).

X-ray of trapped air (1 of 2)

In this antero-posterior xray, one can see that there is so much air in the abdomen, that the diaphragm especially on the left (right of xray) is lifted up, effectively diminishing the volume of the chest cavity and with it, the size of a breath a person can take.

Side view (2 of 2)

A lateral view chest xray shows again the large amount of excess air in the stomach and intestines that the patient must rid herself of via flatulence, typically including through the night, in order to begin the cycle again the next day.

Side view (2 of 2)

The lateral view again shows the line of the thin diaphragmatic muscle above the enormous amount of air in the stomach. The diaphragm inserts on itself so that when it contracts it flattens. That action sucks air into the lungs and simultaneously pushes abdominal contents downward. But how can the diaphragm press down all the extra air? It can't fully, and the inspiratory volume is thereby diminished. The person says "I can't get a deep breath."

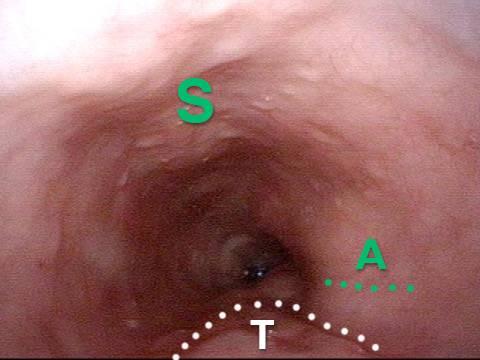

More Interesting Esophageal Findings of R-CPD (Inability to Burp)

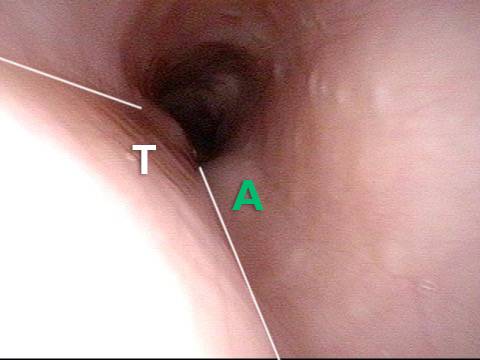

Stretched Esophagus (1 of 4)

Using a 3.7mm ENT scope with no insufflated air, note the marked dilation of the esophagus by swallowed air the patient is unable to belch. T = trachea; A = aortic shelf; S = spine

Stretched Esophagus (1 of 4)

Using a 3.7mm ENT scope with no insufflated air, note the marked dilation of the esophagus by swallowed air the patient is unable to belch. T = trachea; A = aortic shelf; S = spine

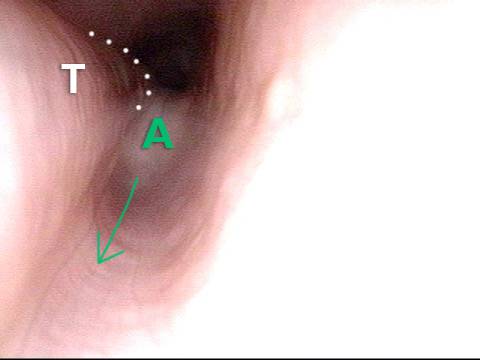

Tracheal Wall (2 of 4)

The posterior wall of the trachea (T) is better seen here from a little higher in the esophagus. A = aorta

Tracheal Wall (2 of 4)

The posterior wall of the trachea (T) is better seen here from a little higher in the esophagus. A = aorta

Over-dilation (3 of 4)

The photo is rotated clockwise at a moment when air from below is pushed upward so as to transiently over-dilate the esophagus. Note that the esophagus is almost stretching around the left side of the trachea in the direction of the arrow.

Over-dilation (3 of 4)

The photo is rotated clockwise at a moment when air from below is pushed upward so as to transiently over-dilate the esophagus. Note that the esophagus is almost stretching around the left side of the trachea in the direction of the arrow.

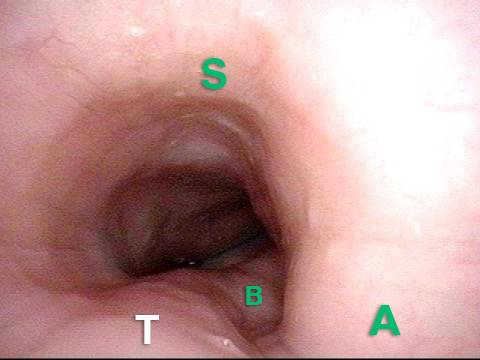

Bronchus (4 of 4)

Now deeper in the esophagus (with it inflated throughout the entire examination by the patient's own air), it even appears that the left mainstem bronchus (B) is made visible by esophageal dilation stretching around it.

Bronchus (4 of 4)

Now deeper in the esophagus (with it inflated throughout the entire examination by the patient's own air), it even appears that the left mainstem bronchus (B) is made visible by esophageal dilation stretching around it.

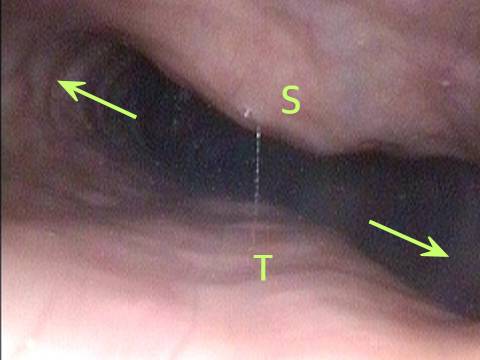

Dramatic Lateral Dilation of the Upper Esophagus

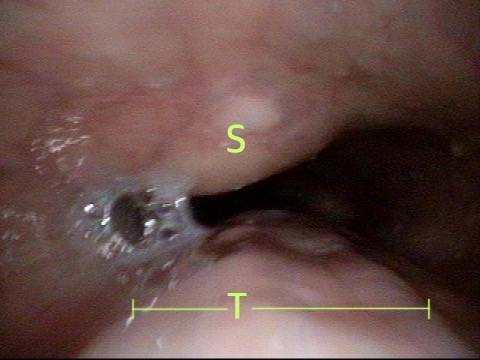

(1 of 3)

This photo is at the level of (estimated) C6 of the spine (at S). This person has known cervical arthritis, accounting for the prominence. Opposite the spine is the trachea (T). Note the remarkable lateral dilation (arrows) in this picture obtained with with no insufflated air using a 3.6mm ENF-VQ scope. It is the patient's own air keeping the esophagus open for viewing.

(1 of 3)

This photo is at the level of (estimated) C6 of the spine (at S). This person has known cervical arthritis, accounting for the prominence. Opposite the spine is the trachea (T). Note the remarkable lateral dilation (arrows) in this picture obtained with with no insufflated air using a 3.6mm ENF-VQ scope. It is the patient's own air keeping the esophagus open for viewing.

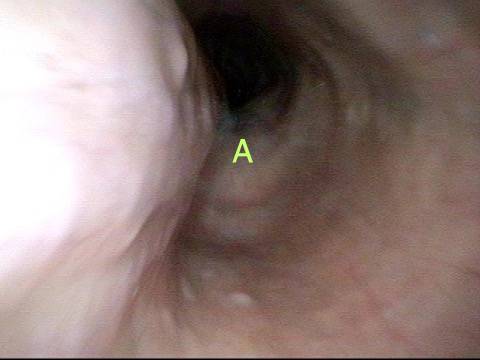

(2 of 3)

At a moment when air from below further dilates the upper esophagus, the tracheal outline is particularly well-seen (T) opposite the spine (S). The "width" of the trachea indicated further emphasizes the degree of lateral dilation, which is necessary because spine and trachea resist anteroposterior dilation.

(2 of 3)

At a moment when air from below further dilates the upper esophagus, the tracheal outline is particularly well-seen (T) opposite the spine (S). The "width" of the trachea indicated further emphasizes the degree of lateral dilation, which is necessary because spine and trachea resist anteroposterior dilation.

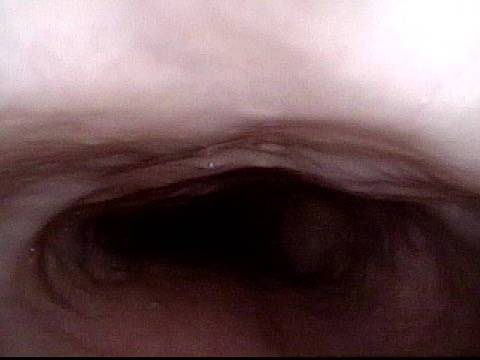

(3 of 3)

Just for interest, at mid-esophagus, the familiar aortic "shelf" is seen. Again, this esophagus is being viewed with a 3.6 mm scope with only the patient own (un-burped) air allowing this view.

(3 of 3)

Just for interest, at mid-esophagus, the familiar aortic "shelf" is seen. Again, this esophagus is being viewed with a 3.6 mm scope with only the patient own (un-burped) air allowing this view.

What the Esophagus Can Look Like "Below A Burp"

Baseline (1 of 3)

Mid-esophagus of a person with R-CPD who is now burping well after Botox injection into the cricopharyngeus muscle many months earlier. The esophagus remains somewhat open likely due to esophageal stretching from the years of being unable to burp and also a "coming burp."

Baseline (1 of 3)

Mid-esophagus of a person with R-CPD who is now burping well after Botox injection into the cricopharyngeus muscle many months earlier. The esophagus remains somewhat open likely due to esophageal stretching from the years of being unable to burp and also a "coming burp."

Pre-burp (2 of 3)

A split-second before a successful burp the esophagus dilates abruptly from baseline (photo 1) as the excess air briefly enlarges the esophagus. An audible burp occurs at this point.

Pre-burp (2 of 3)

A split-second before a successful burp the esophagus dilates abruptly from baseline (photo 1) as the excess air briefly enlarges the esophagus. An audible burp occurs at this point.

Post-burp (3 of 3)

The burp having just happened, the esophagus collapses to partially closed as the air that was "inflating it" has been released.

Post-burp (3 of 3)

The burp having just happened, the esophagus collapses to partially closed as the air that was "inflating it" has been released.

Where have we helped patients burp?

Source: https://laryngopedia.com/inability-to-burp/

0 Response to "Why Do I Continue to Burp"

Post a Comment